The history

A symbol of the Eixample restored for the city

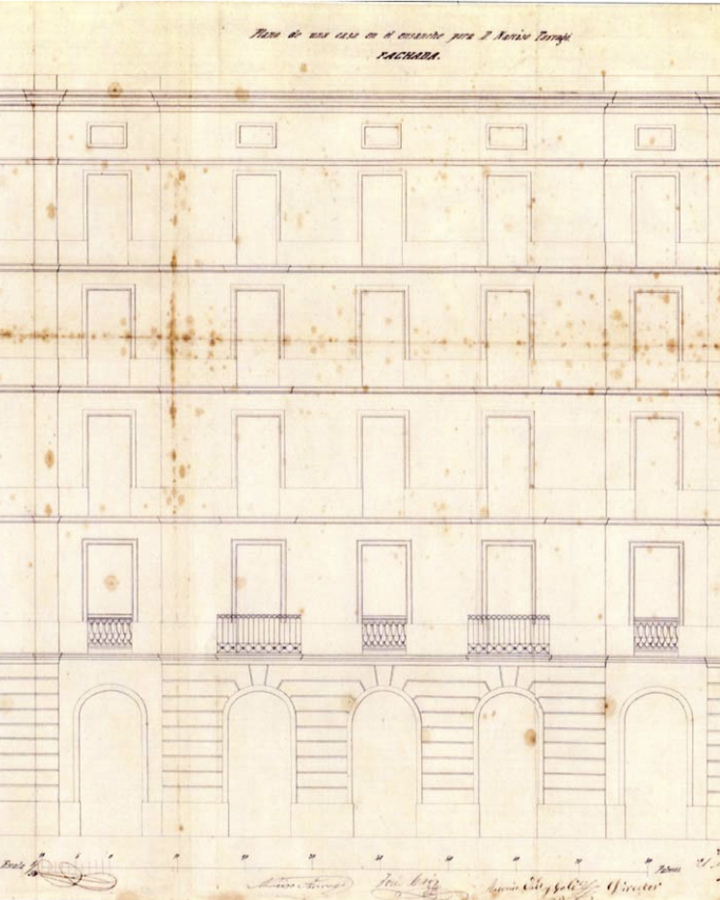

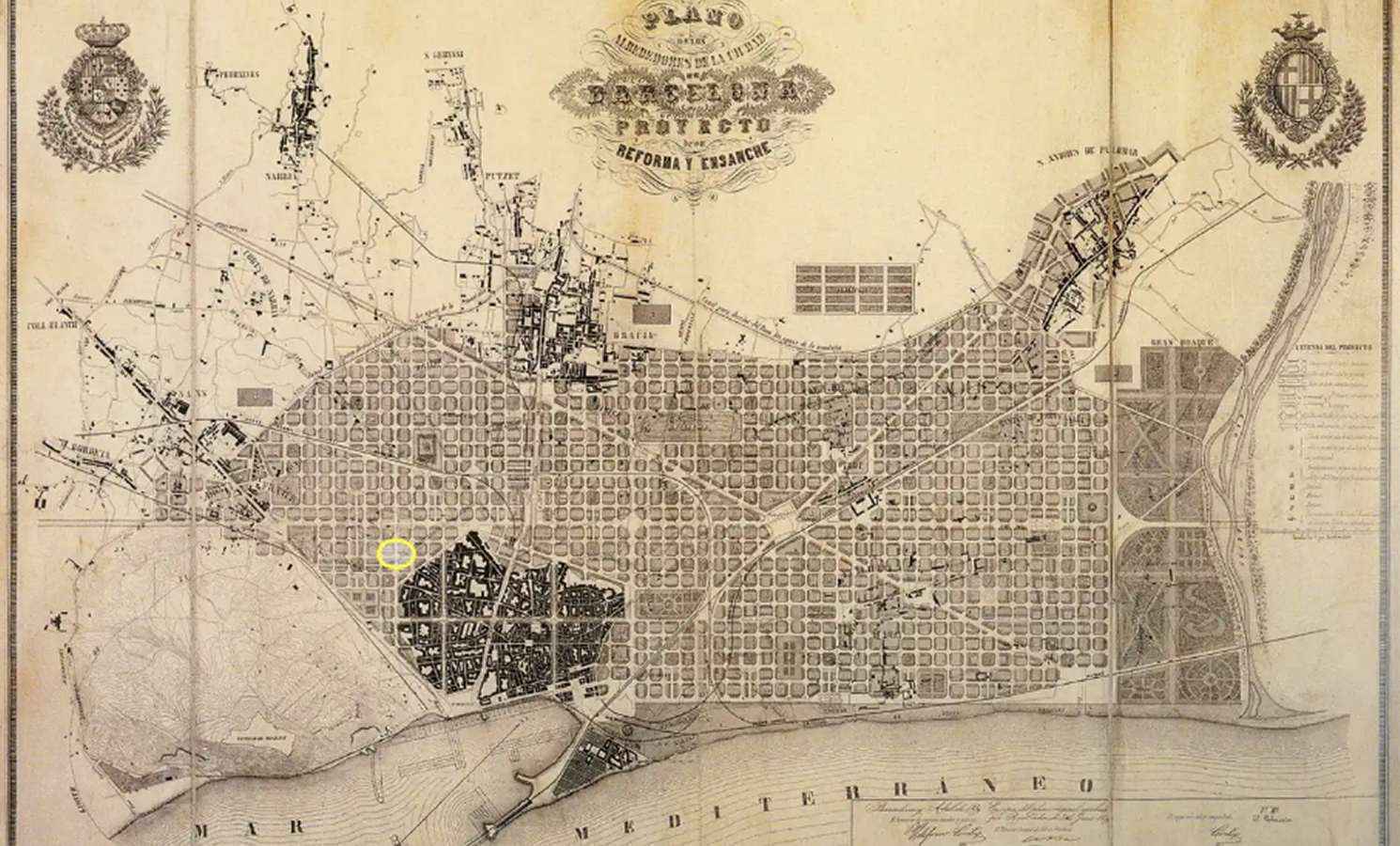

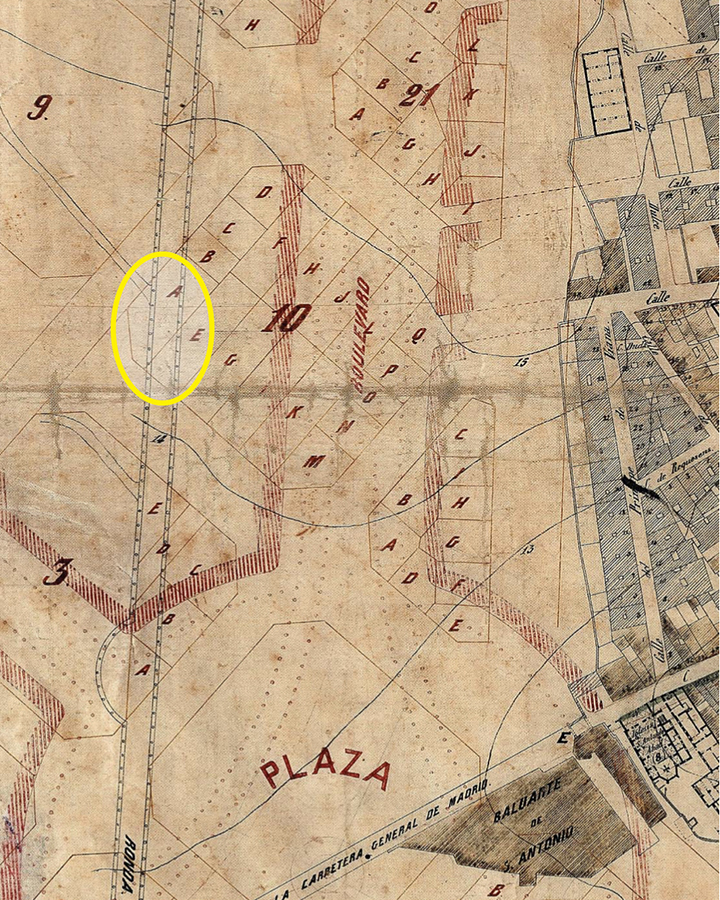

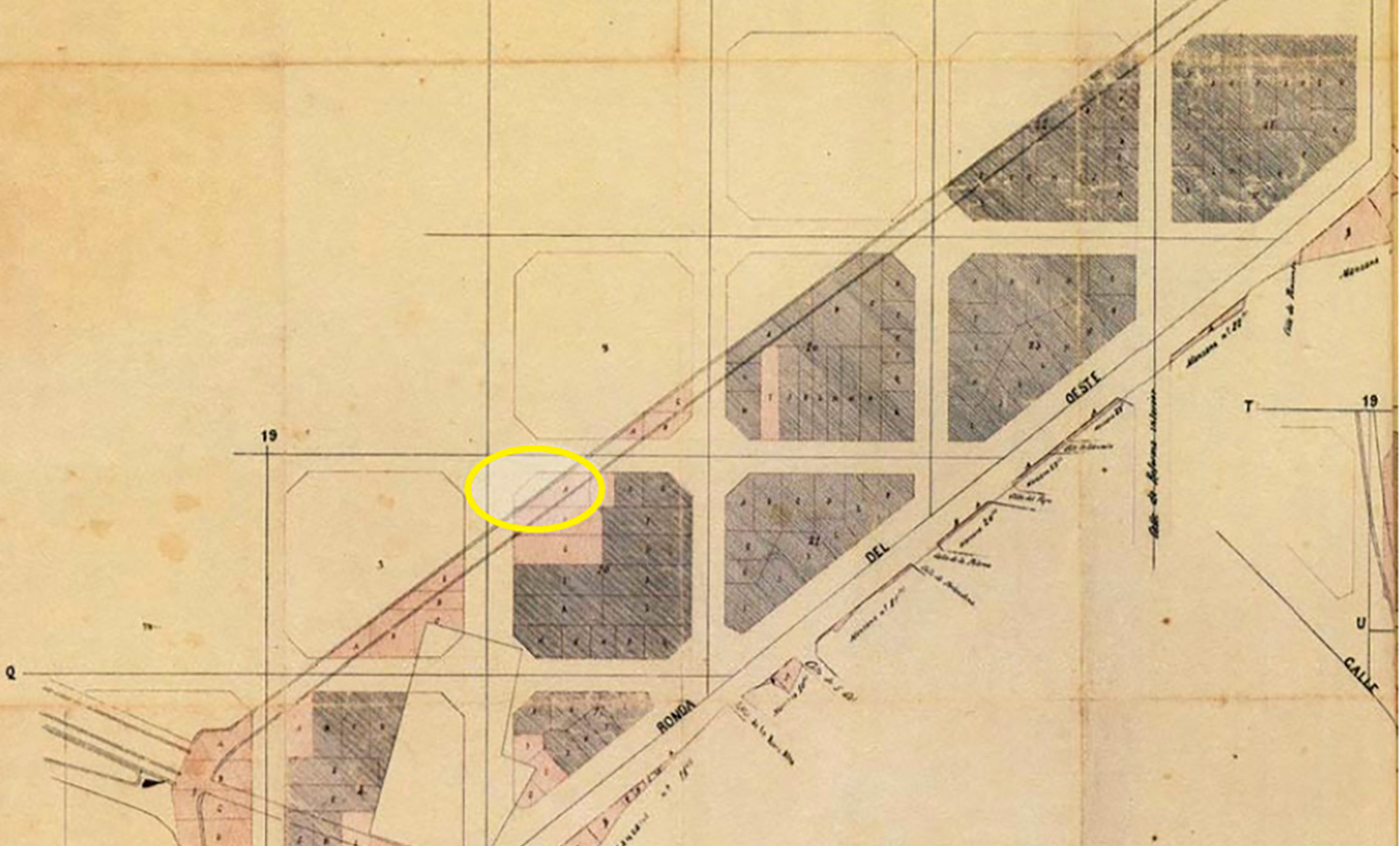

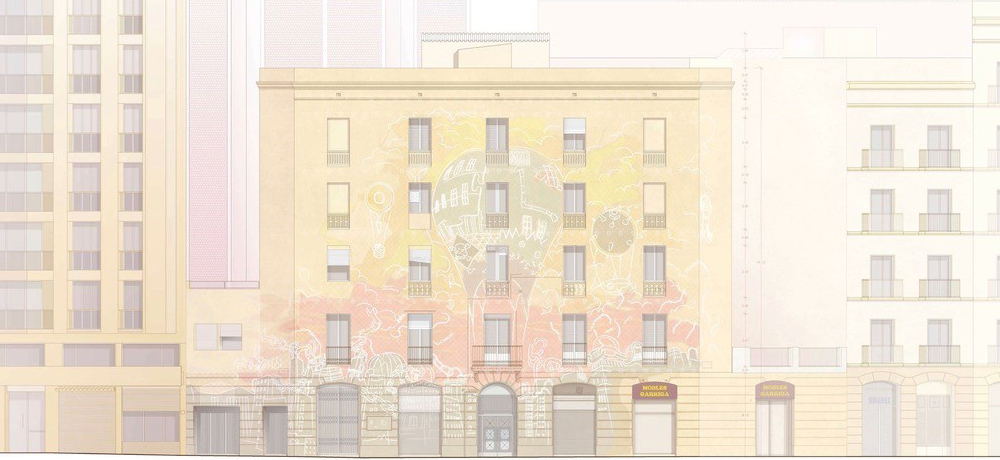

La Carbonería, originally known as La Casa Tarragó, was designed in 1864 by Narciso Tarragó Alexandri and the master builder Antoni Valls I Galí and is thought to be the oldest building in the Eixample district of Barcelona.

In 2015, after a long and eventful history during which the building was badly damaged, La Carbonería was placed under municipal protection and declared an Asset of Urban Interest. This was not only because of the building’s age, but also due to the important historical circumstances that led to its unique form. The owners have now restored La Carbonería to its original splendour, with a project that both reclaims a fundamental part of the city’s history and benefits the local neighbourhood and environment.